Savitri Editing — A Note by Nirodbaran

[Following note records what Nirod had said in one of the meetings in Amal’s place when, on 6 July 1988, the Table of Corrections was being looked into for finalisation. He got exasperated the way things were being conducted and done, and almost wanted to disassociate himself from the work. I recorded his statements the same evening and checked the note with him the next day morning. He agreed to what was shown to him, and also said this was important. Minor editing for the sake of verbal clarity has been done while reproducing the note in the following. ~ RYD]

I am very much hurt when you [referring to Amal’s comment in the meeting] say that I am sitting in judgement on Sri Aurobindo. Surprising that you should have made a statement amounting to this, when you know me very well. If the Table is, as you assert, in full conformity with Sri Aurobindo’s manuscript, then I have no work to do. In fact there cannot be any work for any one. You must clarify this.

If what you are seeing is to be followed I don’t think I have any work to do; nor can I do any in the absence of the original material with me. You are effectively telling that the Table [of Corrections prepared by the Archives editors to carry out revisions in Savitri is final except for minor corrections or revisions at places.

But is it true? Several aspects have now surfaced in the light of recent discussions which even Richard admits. The issues are: copy-text; Nolini’s typescript; fascicles; the first Edition of Savitri that came out before Sri Aurobindo’s withdrawal, in September 1950.

While copy-text, particularly in Sri Aurobindo’s own hand, is of prime importance, it cannot have the absoluteness of value or status. Sri Aurobindo made changes in the poem at every stage it went to him. He heard Part One [the 1950-Savitri] at least three times when it was being printed. And the fact that he was attentive is clear from the complex changes by dictation introduced by him during this process itself.

Secondly, we cannot neglect the Nolini-factor completely. Much that is in the ’50 owes to his effort. I know he used to refer several cases to Sri Aurobindo and make changes under his instruction. How can we ignore this?

Editors of the Critical Edition to some extent acknowledge his contribution — they have retained 300 commas introduced by Nolini — which were not present in the copy-text — but rejected a lot because of — I don’t know why. Is it after referring to the copy-text or is it because of the sense of the passage? A detailed comparison in all those respects is essential. But Richard said the other day that such a task will take 20 years or more. He is impatient to deny the fruits of his labour being held back from the public. Do we play to the public expectation this way? He says he is not aiming at the exalted edition of Savitri. It is good he has said it now, but then he has not defined the scope of his work either.

Several anomalies in the Table pointed out by Jugal have now been accepted by both of you; how can we then say that very little need be done as far as the Table is concerned?

My own readings given to you are based on the data in the Table and the fact that Canto IV of Book Three had appeared in print thrice in Sri Aurobindo’s own lifetime. How can we neglect this fact? If he had no faith in Nolini, no confidence in his capability, why did he give it to him at all?

This arbitrary editorial approach does not appreciate the natural way in which the poem emerged. You are aware of it and our task is essentially to correct some of the very obvious slips that have occurred in the process, and not anything more than that. No mechanical rules should be followed.

You have handed over the responsibility of finalising Part I of Savitri to me. But I thought it appropriate to make my final decisions in the form of a proposal so that we have scope for the discussion. That is why the entries were listed as “suggestions”. You have, however, gone off tangentially giving them the look of aesthetic and personal taste. My own judgement is based partly on the several printed versions in Sri Aurobindo’s own lifetime and partly on the Table of Corrections. Table of Corrections itself doesn’t tell me what is his and what is mine — because of the strange “copy-text” definition.

In the given circumstances it is impossible to carry on the work of ‘looking’ into the entries of the Table of Corrections. We will have to go by scrutinising each entry in full detail, work out the plausibility factor and record it so as our reading.

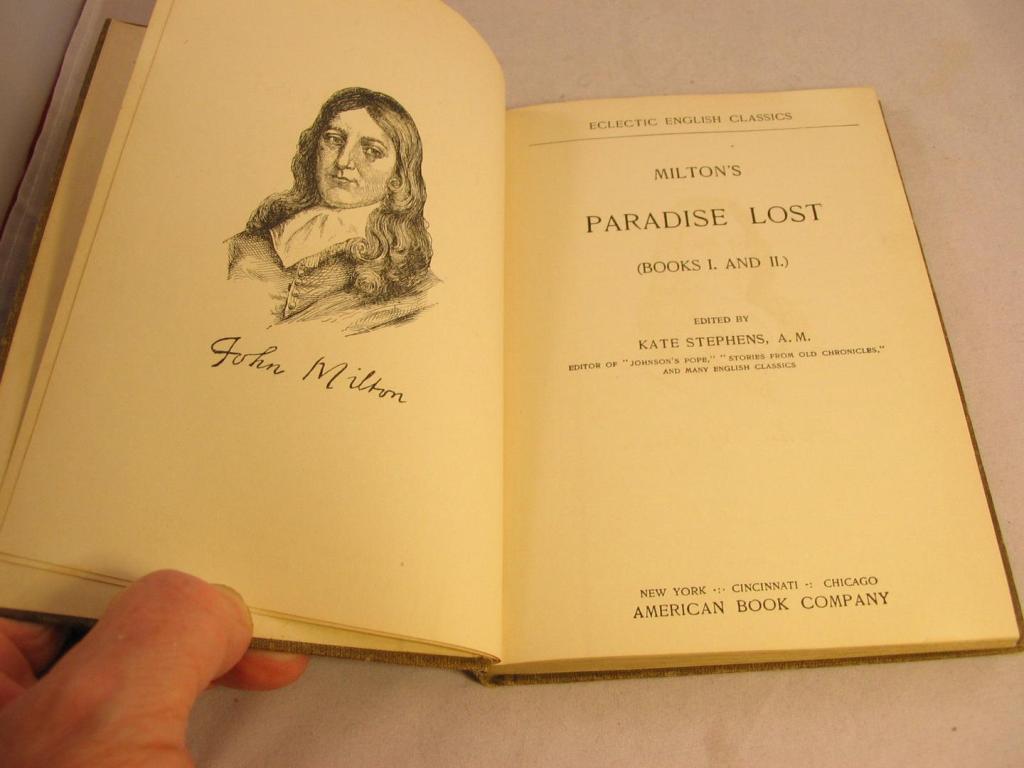

In this context, to shoot out quite away from Savitri, it may not be too much out of place to look at the way a classical scholar of yesteryears looked at Milton’s Paradise Lost. He felt that there were “monstrous” blunders made by the printers and these need be corrected.

Richard Bentley (born Jan. 27, 1662, Oulton, Yorkshire, Eng.—died July 14, 1742, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire) was a British clergyman, one of the great figures in the history of classical scholarship, who combined wide learning with critical acuteness. Gifted with a powerful and logical mind, he was able to do much to restore ancient texts and to point the way to new developments in textual criticism and scholarship.

“From its first publication in 1667, alumnus John Milton’s Paradise Lost has been a poem which inspires critical discussion and learned investigation. In the mid 18th century one editor, Richard Bentley, set out to produce an edition of the epic which would correct the ‘monstrous Faults’ he believed had corrupted the text by its original editors. Bentley is an incredibly interesting character. An eminent classical scholar, he was appointed Master of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1699 but his eccentric manner proved divisive. One of his most unpopular moves was making his son a Fellow of the College at just 15 years of age. This and other ill-advised reforms caused the other Fellows to attempt to oust Bentley more than once but he continued as Master until he died in 1742. Bentley is also a prominent figure in the history of the Cambridge University Press and was largely responsible for its revitalisation from 1696 onwards. It was through the Press that he published this controversial edition of Paradise Lost.

In the preface, Bentley decries the ‘pollution’ of Milton’s texts and throughout the poem makes many additions and emendations to try and restore the poet’s supposed original wording. …”

In the case of Savitri we should recognise the working procedure that was followed. There are drafts in the hand of Sri Aurobindo himself; but then these were quite extensively revised later, by dictation, when the composition was taking the final shape, during the period 1944-50. Come here in the picture the scribe who took down the dictations, the typist, and the press for the publication, the proofs which do not exist now. We do not know whether, immediately after the dictation, this new material was read out to the Poet. Perhaps it was not; it was only after the typescript was read out. At this stage he often added new lines without making any verbal changes in what had existed in it.

It is clear that at every stage the sheets were read out to the attentive Poet when he took the opportunity also to add by dictation new material at every stage. It means, there was always a possibility of natural human slips appearing anywhere, slips being made in the long whole sequence. It is therefore quite reasonable and legitimate to check the final printed version with the manuscripts wherever possible. But there also enters a subjective element as regards the editors handling the complicated task when several manuscripts of a given passage do exist. Could this subjective element fall in the Bentley-category. At times it seems so.

The reader or conscious student of Savitri is now completely helpless, that he has just to accept what has been given to him by these editors. He may have very sincere genuine doubts or considerations but he has no way of clearing his apprehensions.

It is in that respect we must admire Nirodbaran’s Note on Savitri-Editing. That should mean, as far as revisions are concerned, something more as a detailed presentation must be done. All the data should be made accessible for any critical study. It may take “twenty years” but that seems to be very necessary. Why should that matter? We may supportively refer to this:

Editing Paradise Lost

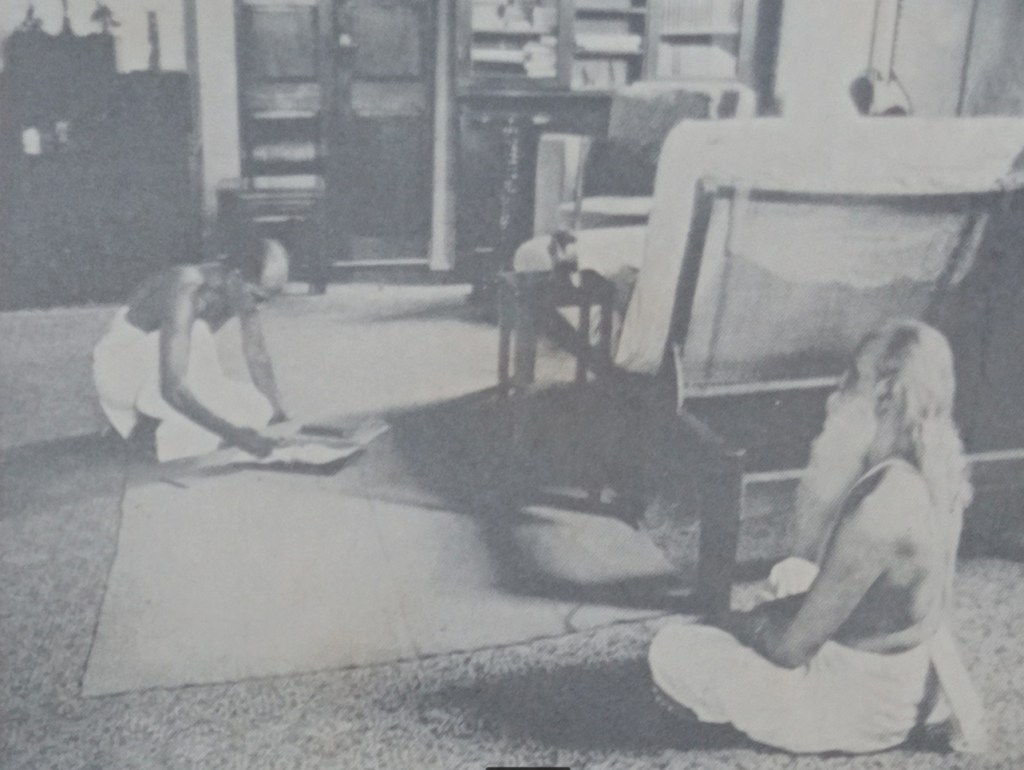

Here is a setting recreated: Sri Aurobindo, sitting on the bed, used to dictate Savitri to Nirod, Champaklal in attendance for any needs.

Source: Twelve Years with Sri Aurobindo by Nirodbaran

A Note from Nirodbaran and Amal Kiran

But we do not have any written letter or note from any competent authority for them to look into the Table of Corrections and give their recommendation. Bureaucratically there are too many loose ends in the entire affair. Perhaps all was done with mutual understanding and appreciation, as in the Ashram-family. But the matters are becoming now serious at a different level. How did Amal come into the picture at all, with what locus standi, even as he had handled the two earlier editions, of 1954 and 1972? Was this long and intimate association with Savitri the only reason? Nolini Kant Gupta had specifically and clearly told Jayantilal, the Archives incharge: “If Nirod approves.” But the Mother had strongly told Amal that she would not allow him to change even one comma.

Leave a reply to justynjedraszewski Cancel reply