I have understood myself

उमगले माझेपण माझे मलाच

बसलो होतो प्राचीन आम्रवृक्षाच्या छायेत,

आणि उमगले माझेपण, माझे मलाच;

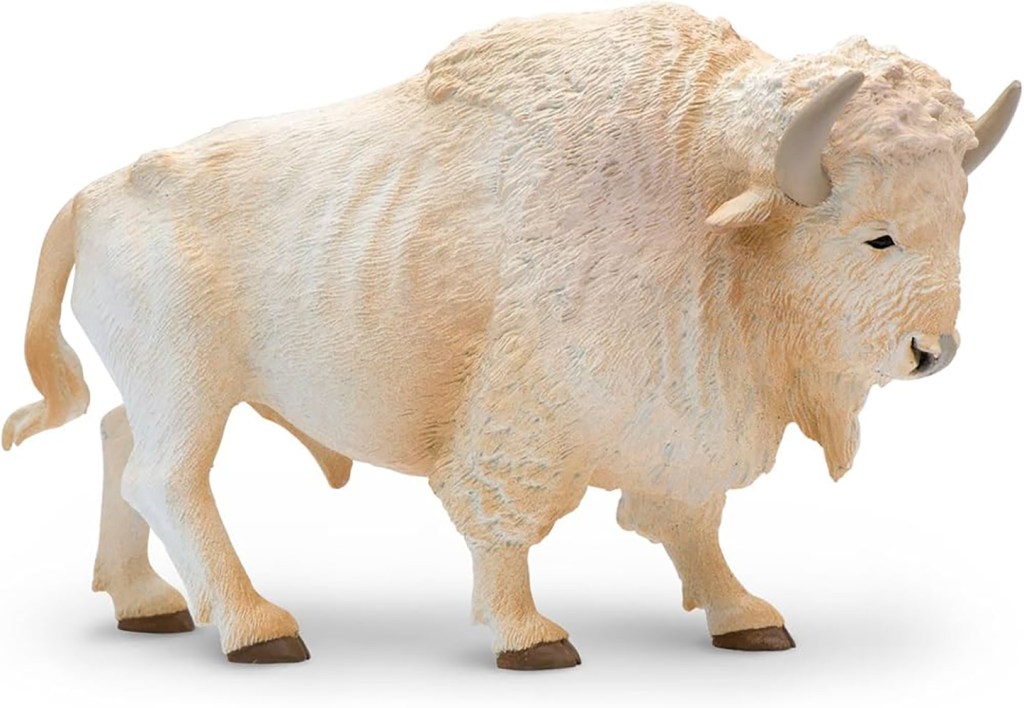

पाहता पाहता तेथे आला शुभ्रवर्णी रेडा,

आणि जसा आला वदु लागला वेदमंत्र;

सांगे, वदविले तें माझ्याकडून योगियाने,

उदात्त छंद, सुश्राव्य, महान, अर्थही गहन;

सर्वत्र, त्यांच्या लयीत फिरती विश्वाची चक्रे,

जसा अनाहत ध्वनी वेगात पसरे सगळीकडे;

पण बोले ऋषी दीर्घतमस चातुर्वाणीचें,

एकची असे इथे, त्या तिघी पलीकडे, गुहेत;

ओळखतो मी त्यांनाही पण उत्सुकता की

इथे अवतरेल का जगती तिच्या छंदासह;

येई पश्यन्ति परावानीच्या प्रखर उजेडाने,

बघत बघत, घेत घेत, सर्जनशील आनंद;

कदाचित तेव्हा उमगेल माझेपण मला,

सत्यात वाढण्यासाठीच तर आहे मी इथे.

7 May 2025

Dirghatamas: Rig Veda I:164:45

च॒त्वारि॒ वाक्परि॑मिता प॒दानि॒ तानि॑ विदुर्ब्राह्म॒णा ये म॑नी॒षिणः॑ ।

गुहा॒ त्रीणि॒ निहि॑ता॒ नेङ्ग॑यन्ति तु॒रीयं॑ वा॒चो म॑नु॒ष्या॑ वदन्ति ॥ १.१६४.४५

चत्वारि । वाक् । परिमिता । पदानि । तानि । विदुः । ब्राह्मणाः । ये । मनीषिणः ।

गुहा । त्रीणि । निहिता । न । इङ्गयन्ति । तुरीयम् । वाचः । मनुष्याः । वदन्ति ॥ R.V. 1.164.45॥

catvāri | vāk | pari-mitā | padāni | tāni | viduḥ | brāhmaṇāḥ | ye | manīṣiṇaḥ | guhā | trīṇi | ni-hitā | na | iṅgayanti | turīyam | vācaḥ | manuṣyāḥ | vadanti |

Four are the definite grades of speech; those who are wise know them; three, deposited in secret, indicate no meaning; men speak the fourth grade of speech.

Speech (वाक्) is graded (पदानि) as four regulated levels (चत्वारि परिमिता) ; the seers or the poets who have intuition know (विदुः) them. Three of them (त्रीणि), not clearly known (निहिता –न – इङ्गयन्ति), concealed in the cave (गुहा), do not move; the fourth of the speech (वाचः तुरीयम्), men speak (मनुष्याः वदन्ति).

Leave a comment